My wife and I married in 1976. When our first child was born in 1984 we asked ourselves a question common to young parents in America, "Where should we send our kids to school?". This was something we took very seriously, as most parents do. My parents said "why don't you move to a nice suburban school district?". In some sense, they were suggesting we do what they did in the 1960's which was to move out of the city to a middle class suburb and "check the box". They believed if it worked for their sons, it would work for their grandchildren.

What I mean by "check the box" is that you move to a homogenous suburb of like minded people with what is considered a quality school, pay your taxes, and sleep good at night knowing you've checked the education box. Your children will do fine. And since these were public schools, there was no cost over and above their property taxes.

As usual, we did not agree with my parents... for a number of reasons. We both grew up in the suburbs (my wife outside of Baltimore/Washington and myself outside of Cleveland). We both disliked the suburbs for various reasons and chose to attend college in the city. We met at Carnegie Mellon University and decided to make Pittsburgh our home. We bought a house in the East End (Wilkinsburg) and have lived there for 35 years. Here's what we love about living in the city.

- Living in a community that was socioeconomically, racially, culturally and age diverse

- Outstanding public transportation

- Walking to shops, movie theaters, libraries, the post office

- The Carnegie Museums

- The Theaters - PPT, City Theater, Pittsburgh Opera, PICT

- The Universities

- Schenley and Frick Park

- Living in a very affordable 100 year old Victorian home with leaded and stained glass, oak fireplaces, wood floors, high ceilings, front and back porches and a three car garage

- Amazing architecture

- Wonderfully diverse restaurants

- Relative proximity to where we worked (very short commute)

- Squirrel Hill, Greenfield, Southside, Shadyside, Oakland, East Liberty, Friendship, The Strip, Lawrenceville, Bloomfield, Polish Hill and all the neighborhoods

The quality of Pittsburgh education at the time depended upon what neighborhood you lived in, or what magnet school you could attend, or what program (such as gifted or scholars) your child was eligible for. Our friends confronted the same education landscape and worked hard to get it right. Most went to public schools. Some went to private schools. And some moved to get into a particular school. Some even used a relative's address to get into a particular school.

Our education journey was difficult, but doable, especially if you had financial means. It was also helpful that I was an educator so I had a deeper knowledge of the system than most parents.

It is much harder for a parent to maneuver through the urban education options in 2014. What would my wife and I do now if we had to find a school for our children? Why is it more difficult? Basically, the economic, population and housing trends that began when we were born continues to the present day. These trends have had a devastating effect on urban schools.

In the 1950's Pittsburgh, like Cleveland, Buffalo and Detroit, was in its heyday. Post war growth had the city's industry humming with new houses, new cars, new highways, bridges, office buildings, skyscrapers, etc. Cities were thriving. At the same time, the great American Dream was evolving. The advent of the American highway system, the proliferation of automobiles and the creation of a robust middle class provided a level of mobility never seen in our history. People began moving to the suburbs.

|

| The Growth of Pittsburgh |

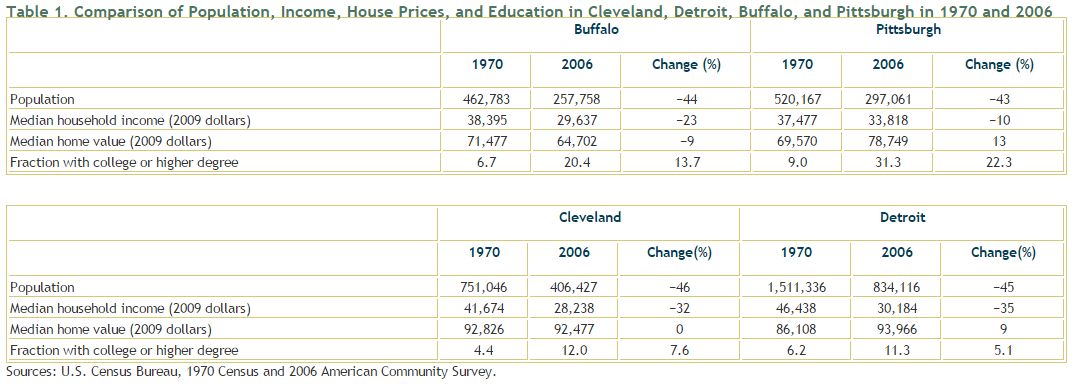

The migration to the suburbs was exacerbated during the 1960's by civic unrest in the urban core. This volatile decade was highlighted by the Civil Rights movement, an anti-war movement and a labor movement that was centered in our cities. Riots in urban ghettoes, marches on university campuses, a war in Viet Nam, numerous labor strikes and four assassinations were played out on the 11:00 news. Many families began to fear urban life and those with means moved to the suburbs. The chart at the right shows the decline in Pittsburgh's populations starting in 1950. By 1970 the city lost over 150,000 people from its height in 1950. And this was before both industrial and educational challenges raised the stakes on urban living.

From an urban education perspective, the 1970's and 1980's were the decades of integration. 20 years after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, the courts came to the conclusion that voluntary integration would not occur. Forced busing attempted to provide equal education to all students. It was naive to think the courts could force integration. Parents fears, beliefs, biases and limited experiences were too great to overcome, in what was perceived as a court decision that overruled personal choice. Rather than integrate, many people of means moved to the suburbs.

From an urban economic perspective, the 1970's and 1980's were the decades when industry left the cities. Steel mills, automobile plants and related industries shut down and moved out. It is estimated that over 150,000 people were laid off by the steel companies in Pittsburgh in 1982-3. People left the city to seek jobs elsewhere. The people that left were either working middle class families with means who moved to the suburbs or out of work steelworkers who moved to find jobs elsewhere. This left a city with a diminished tax base, empty houses, shrinking human capital and a feeling of devastation.

|

| Urban Decline in Rust Belt Cities |

Decades of unrest, loss of jobs, loss of industry, forced integration and mobility to the suburbs created an urban core that was decaying. By 2010 Pittsburgh had lost over 50% of its population.

Steel Works

Then and Now...

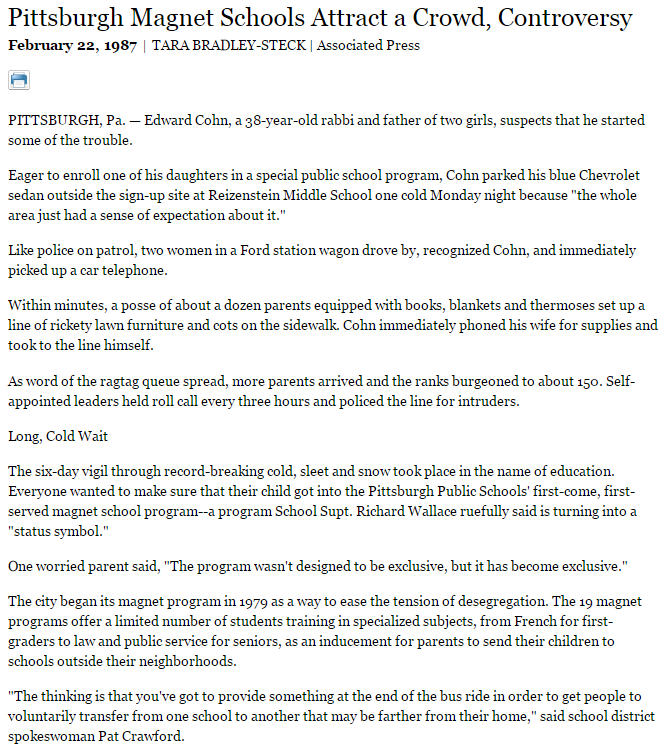

It is not surprising therefore, that urban school districts were confronted with a complex problem. Loss of resources, working with a more needy student population and a diminished economy put the school districts at a huge disadvantage. That is what confronted parents as they attempted to choose a school for their children. So let me tell a story about what parents will do to find a quality school for their children. The year was 1987.

|

| LA Times Article |

The Pittsburgh Public Schools implemented a magnet program to encourage voluntary integration. The magnet schools had a special emphasis (computer science, foreign language, classical studies) and were designed to be racially balanced (50% black, 50% white). Sign up was on a first come, first served basis.

|

| 1987 Magnet Signup |

This is the extent that people will go to find a quality school for their child. It also raises key points about school choice in an urban setting. It proved that parents were willing to send their children to integrated schools... with two caveats. First, the races have to be balanced. By creating racial quotas the magnets by design were racially balanced. This was needed to get families over their fears pertaining to mixing races. Second, the fact that parents went out of their way to sign their children up for a school (rather than default to their neighborhood school) suggests that the magnet parents shared a common desire for quality education. Simply put, parents were willing to put their children on a bus, leave their neighborhood and attend a magnet school if the school was balanced racially, was of a high quality and had parents who actively made the choice to attend the school. They made this choice rather than move to the suburbs.

Imagine... waiting 6 days and nights outside in January.

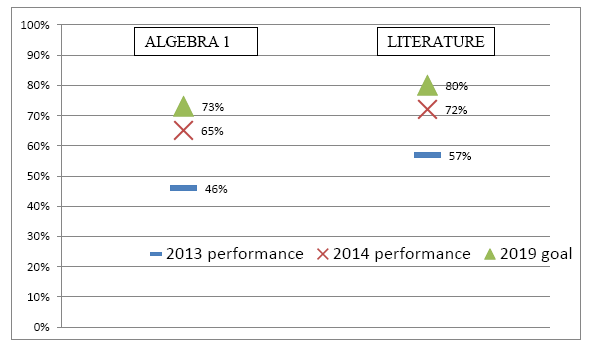

So how does a parent make the decision in 2014?

|

| Pittsburgh East End Schools - Public, Charter, Private |

The chart above summarizes the current public, charter and private schools in Pittsburgh's East End. As you can see it's a daunting list. Neighborhood schools, magnets, partial magnets, charters, parochial ($4,000-18,000 per year), university schools ($13,000 per year) and private schools ($16,000 - 28,000 per year). And if you have more than one child, the cost to go to private schools doubles or triples.

It is not surprising that there is a huge amount of variability between these schools. Some are all white... some are all black. Some are poor... and some are wealthy. And some are diverse. Some produce amazing student achievement, and some are the lowest in the state. The variation of schools in both the city and the suburbs suggests that education in America is balkanized. So we are back where we started... the burden is on the parent to figure it out and get the best education for their child. Thus, more and more people choose to "check the box" and move out of the city to an affordable suburban school district.

I have an adage that I subscribe to. People, parents, politicians do a lot of talking. They talk as if they are conservative or liberal, reactionary or radical, libertarian or tea party. I don't listen to what they say. I watch where they send their children to school. People don't gamble with their children. They shouldn't. But they do select schools based on their biases, their fears, their experiences and sometimes, what's easy. I can make an argument for "checking the box" and attending a suburban school from a variety of perspectives. Free education. A relatively good quality. Convenience.

As is true of any school choice there are drawbacks as well. Suburban schools were always considered safe, but that is less true now (see The Evolution of Violence in Schools.) And in suburbia, conformity is the norm. It can be a difficult passage through a suburban school if you are a special needs child, or have ADHD, or are in a small minority (race, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation). But as long as you fit in, your parents can "check the box".

I am suggesting that parents who want to live in the city should engage in their child's education, stay in the city and help make our schools better. Education is so much more than learning the essentials (reading, writing and arithmetic). It is about learning how to collaborate, becoming tolerant of individual differences, gaining value from diversity and different points of view. It is about becoming culturally aware through museums, libraries, architecture and the arts. It is about experiencing the culture of other religions, races, classes and ethnicities. It is about becoming part of a greater community, society, country and world. And you can get a rigorous academic experience if you work at it.

You are fooling yourself if you move to a suburban school and all you do is check the box. You are fooling yourself if you send your child to any school and all you do is check the box. In America, a child's education is determined by their parent, not the government.

I finish with a recent letter to the editor in the Post-Gazette. The letter was sent by a colleague of mine and an excellent teacher I worked with at City High. She talks about her struggle to find a quality school for her son. And she does a superb job of articulating the broader issue. By no means could she be accused of "checking the box."

Woodland Hills’ history shows parents can demand quality

As a parent of a student in the Woodland Hills School District and as an educator, I read with interest “Woodland Hills Strives and Struggles to Achieve Equality” (Oct. 5). Most compelling was that the initial drive to ensure an equal education for all students came not from politicians or educators but from parents.

My husband and I have struggled since our son neared the end of his preschool years to determine the best educational choice for him from myriad options: public, private or charter, homeschooling or unschooling. Some counseled that we move, others that we budget to allow for a private education. We entered charter lotteries and bore the disappointment of waiting lists.

Through it all, two things remained constant. One is that we have been consistently impressed and grateful for the remarkable talents and professionalism of the teachers and administrators at Woodland Hills. Another constant is our belief that it is not just our child but our neighbors’ children, who all deserve a quality education. We may pick up and move; we may scrimp to afford a private school education, but what about the families who may not have those options available to them?

Families must make the decisions that they can live with and that work best for them. I look for my inspiration to the families who fought for the original desegregation order for providing a model of how dedicated parents can organize and demand a rigorous and enriching education for all students.

(Post-Gazette, Oct. 15, 2014)