"This law will usher in the most sweeping, positive changes to public education we've seen in two decades." (Randi Weingarten, President, American Federation of Teachers)

“This new law is a well-deserved victory for our nation because the Every Student Succeeds Act will create greater opportunity for every student regardless of ZIP Code,” said NEA President Lily Eskelsen García. “Educators welcomed the end of No Child Left Behind and the beginning of a new era in public education in schools.”

"It's empowering us state and local decision-makers to develop our own system for school improvement," Pennsylvania's Education Secretary Pedro Rivera said. "It's creating more access to high-quality preschool programs. It's understanding that there's far too much of an onerous burden of testing on students and teachers. So it gives a little more flexibility to how we assess education and school districts across the state."

John Callahan, assistant executive director of the Pennsylvania School Boards Association, said the Pennsylvania Department of Education has already begun to implement some of the provisions seen in this “next generation of the bill.” “This is a huge bill,” he said Wednesday. “There’s a lot already that we do. But the bill acknowledges that there are other ways to measure school district and student success in the classroom than by testing.”

It is hard to find a public educator or a parent in America who is upset about the demise of No Child Left Behind.

So let me tell you what the new Every Student Succeeds Act will do. It will turn the clock back to 2000. That's it.

Let's put this new legislation into its historical context.

According to the tenth amendment to the U.S. Constitution:

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

Public education is not a power delegated to the federal government. Thus it defaults to the individual states. Consequently, for much of the history of our republic, the federal government has had little input into public education. This changed in 1954.

According to the fourteenth amendment to the U.S. Constitution:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

The application of the 14th amendment (equal protection) in the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, was the beginning of the federal government's involvement in public education. This court case looked at the issue of segregated schools (by race) and whether they offered "equal protection" under the law. Counter to the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling where "separate but equal" was allowed in public accommodations, the court decided that "separate but equal" was not acceptable in public education. As a result of the opinion, the Court ordered the states to integrate their schools "with all deliberate speed."

10 years after the Supreme Court decision, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed. This historic legislation "prohibited discrimination in public places, provided for the integration of schools and other public facilities, and made employment discrimination illegal." It should be noted that in the period between the Brown v. Board ruling and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 there was little or no effort to actually integrate public schools. America was not ready for integration.

Starting with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, our country, led by President Lyndon Johnson, entered a decade of progressive politics that addressed concerns pertaining to under served populations (i.e. blacks, women, disabled and the poor). In 1965 the federal government passed the first Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). This act created the Title I program providing federal funding to school districts with high levels of student poverty. Since 1965, Title I has provided federal dollars that were often spent on reading specialists, paraprofessionals and remedial materials for reading and mathematics. The ESEA is periodically reauthorized with changes and improvements, often based on the desires of the President and the Congress at the time.

|

| 2001 No Child Left Behind sign into law |

Upon taking office President Bush expressed his concerns about public education. He argued that the ESEA in general and Title I in particular were not terribly effective. By nearly any measure, poor, black and disabled populations lagged far behind their peers. The question President Bush (and Senator Ted Kennedy) raised was how could school districts be held accountable for using their Title I funds to raise achievement for all students.

Bush, working with Senator Kennedy, rewrote and passed the ESEA of 2001 entitled the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB). Bush and Kennedy felt the need to put teeth into the Title I program. For years the government spent billions of dollars supporting education for students in poverty, but the achievement gap barely budged. The 2001 version of the ESEA, entitled No Child Left Behind, demanded that every state, district and school test students in grades 3-8 and 11 in reading and mathematics, post their test results publicly and hold accountable school districts and states for eliminating the achievement gap (between blacks and whites, poor and rich). This was the start of the high stakes testing era.

Every state created its own assessment system and had it approved by the US Dept. of Education. These assessments consisted of a single criterion referenced multiple choice test given once a year in grade 3-8 and 11 in reading and mathematics. Every year a benchmark had to be reached in order to obtain "Adequate Yearly Progress" (AYP). The benchmark was the % of students who were Advanced or Proficient on the state test. The chart at the right shows the AYP benchmark that had to be achieved by a given year. As you can see the benchmarks in the first few years were low. It did not rise above 54% for both reading and math for 7 years (2008). It then rose sharply to 100% in 6 more years (2014). To reach AYP a district not only had to meet these benchmarks in aggregate, but they had to meet them within subgroups for race, socioeconomic status and special needs students (only if you had more than 40 students in the subgroup.)

Every state created its own assessment system and had it approved by the US Dept. of Education. These assessments consisted of a single criterion referenced multiple choice test given once a year in grade 3-8 and 11 in reading and mathematics. Every year a benchmark had to be reached in order to obtain "Adequate Yearly Progress" (AYP). The benchmark was the % of students who were Advanced or Proficient on the state test. The chart at the right shows the AYP benchmark that had to be achieved by a given year. As you can see the benchmarks in the first few years were low. It did not rise above 54% for both reading and math for 7 years (2008). It then rose sharply to 100% in 6 more years (2014). To reach AYP a district not only had to meet these benchmarks in aggregate, but they had to meet them within subgroups for race, socioeconomic status and special needs students (only if you had more than 40 students in the subgroup.)NCLB was designed as an accountability measure, not as an educational or pedagogical intervention. The program was punitive in its approach. Schools and districts that did not achieve "Adequate Yearly Progress" would be placed in "warning". Every consecutive year a school did not attain AYP, they would head down the list into a more critical category. After 5-6 years if a school found they were in Corrective Action II, students would be allowed to attend a different district school that had better results (if such a school existed.) As one might imagine, the schools that were in Corrective Action worked with the poorest, most needy populations.

Let's compare and contrast two Allegheny County school districts that were at either end of the income spectrum.

|

| 2004 Rand Report |

The following chart represents the Mt. Lebanon School District AYP information for the same year for Reading in grades 5, 8 and 11. This provides a clear contrast from the Pittsburgh Public Schools (or any other urban school district in PA). As you can see, over 86% of Mt. Lebanon students were proficient in reading and mathematics (separate chart). Clearly these were extremely high scores (in only the second year under NCLB.) Note that Mt. Lebanon had no black or hispanic students, and only 25 economically disadvantaged students (2%). Not only did Mt. Lebanon make AYP in 2004, their 2004 scores would qualify for AYP up to 2013.

|

| Mount Lebanon 2003-04 Report Card |

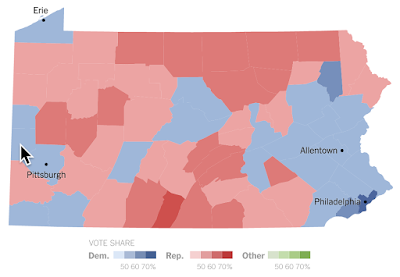

This Pittsburgh - Mt. Lebanon comparison was a typical urban - suburban contrast. As you might imagine, during the first few years of NCLB, it was the Title I urban poor schools that did not attain AYP. They were the schools listed in the newspaper headlines. This confirmed the public's belief that the poorer districts in Pittsburgh (Wilkinsburg, Penn Hills, Woodland Hills, Mon-Valley Schools) were "bad schools". And the highest performing schools (correlating perfectly with income) proved that white suburban schools were "good schools".

Who were we kidding? AYP - Adequate Yearly Progress was not a measure of school quality, teacher ability or student ability. Research on standardized testing and achievement gaps suggests that test scores are highly correlated with family income, living conditions and parent level of education.

Actually, Adequate Yearly Progress is a misnomer. It was not measuring progress from year to year. It was measuring the percentage of students in a school district who were proficient. Pennsylvania realized that it was unfair to evaluate schools and districts simply by the percentage of proficient students. The state petitioned the federal government to allow Pennsylvania to grade schools based on student progress from year to year. The states analysis would focus specifically on how much the school and its teachers improved student achievement from one year to another.

They were turned down by the U.S. Department of Education. Although Pennsylvania developed and used PVAAS (Pennsylvania Value-Added Assessment System) internally, the feds never allowed it for AYP. The point of using a Value Added model of assessment was to acknowledge that, based on many variables (external to school), all students do not start school at the same skill level. Thus testing systems that are used to evaluate schools should be measured based on growth (value added), not on achieving proficiency on a single test. Certainly, not in the elementary and middle school grades.

Ultimately, by using a single criterion referenced test score to measure AYP, the results were a self-fulfilling prophesy. From the start of NCLB in 2002 until 2012 AYP identified "good schools" (suburban, affluent) and "bad schools" (urban, poor). This appeared to confirm long term race and class based stereotypes.

But something happened in 2012 that shook everyone up. Middle and upper class suburban schools began to not make AYP.

First, the top schools did not make AYP because of their special education students. Then, in 2013 and 2014, they did not make AYP because the benchmark was unrealistically high (over 90%). Now suburban schools began focusing on teaching to the test. Due to state fiscal problems attributed to pensions, taxes and an economic recession, state funding for public education was reduced. Lower revenues and narrowly focusing on test results hurt other areas of study. Cuts were made in the arts, physical education, foreign languages, sports and extracurricular activities. Suburban parents were up in arms. They demanded that their children be allowed to opt out of the test. They created advocacy groups calling for a stop to high stakes testing and ending national standards (Parents Against Common Core).

Since 2009, the Obama Administration had talked about a new ESEA, but could not interest Congress in this endeavor. Starting in 2012, with the middle class, suburban backlash against NCLB, something had to be done.

"in 2012, the Obama administration began offering flexibility to states regarding specific requirements of NCLB in exchange for rigorous and comprehensive state-developed plans designed to close achievement gaps, increase equity, improve the quality of instruction, and increase outcomes for all students. Thus far 42 states, DC and Puerto Rico have received flexibility from NCLB".(http://www.ed.gov/esea).The meaning of "flexibility" is that waivers were given with respect to AYP as long as states implemented strict teacher evaluation protocols that were partially based on student achievement on these tests. Once again a punitive approach to school reform. This time they focused on teachers implying they were the problem.

It was becoming apparent that NCLB, a testing program founded on the belief that public accountability would ultimately force Title I schools to succeed with its students, was not working.

First, it made public the fact that a large number of schools working with poor and at-risk populations were not succeeding. These schools, that work with the most impoverished populations, looked terrible, especially in comparison to wealthier communities. This had a crushing effect on students, parents, teachers and administration who were part of these schools.

Second, NCLB provided no additional resources, expertise or suggestions as to how to improve public schools that were working with students who were poor and at-risk.

Third, low achievement in urban public schools opened the door to charter schools that were able to develop new models of education from scratch, without legacy systems like unions, school boards and out of date curricula. This also drew additional revenues and students away from the urban public schools.

Finally, once NCLB began to negatively effect white, middle/upper class families, it created a backlash against both federally dictated learning standards and high stakes testing.

What a mess. Everyone who mattered politically (whites, middle/upper classes, politicians, unions, school boards, progressives and conservatives) had it with the testing and the federal government's attempt at "education reform".

And that brings us to the new ESEA - the Every Student Succeeds Act. Here is a summary of what the Act puts in place.

- District/school evaluation is now strictly a state responsibility. Every state must continue to test students in reading and math in grades 3-8 and once in high schools. And test scores must still be broken out by school and by subgroup. However, each state may choose their own accountability system, benchmarks, standards, etc. The federal government has no role in school/district evaluation, testing or improvement other than to make sure the states are doing their job. However, there are no means for the feds to hold the states accountable (other than through the courts.)

- Guidelines (suggestions) are made for school/district accountability systems. However, there is no recourse if states do not comply with these guidelines.

- There is no role for the federal government in teacher evaluation.

- States and districts will use locally developed interventions in the bottom 5% of schools. Also schools will be flagged where subgroups are chronically underachieving. There is no role for the federal government in these schools other than to provide Title I funds. And there is no clear process for what to do with a school that does not improve.

- Concerns about equity are addressed via "preschool development grants" which has been reassigned to HUD, monies set aside in Title I to address the lowest performing 5% (up to 7% of the Title I budget) and the inclusion of previous School Improvement Grants into the overall Title I budget.

This is what Title I and ESEA looked like in 2001 prior to NCLB. Schools remain segregated, the lowest achieving schools are urban, primarily black, poor and filled with special needs students. Title I dollars will go to these schools and be used for teaching aides, reading specialists and reading recovery programs. The states testing programs (which existed in Pennsylvania starting with TELLS in the early 1980's) will continue, but with much less accountability or downside. And education control is local.

Not once during this maddening ordeal, starting with Title I in 1965 and leading through NCLB in 2001, has the federal government or individual states offered comprehensive financial support to poor underachieving schools for:

- Social Workers, Nurses, Nutritionists, Counselors and Psychological Services to help students manage their mental, physical and emotional health as they navigate through poverty, violence and broken families;

- Identifying, hiring and keeping High Quality Teachers and Administrators to work in poor, underachieving schools;

- Books, home libraries, technology and various learning materials to be provided to students, used in school and kept permanently in students homes;

- Free post high school education;

- Free Preschools;

- Free Health Care for children;

- Free year round schooling; and

- Replicating quality, proven successful inner city public, charter or private schools.

We know what works with at-risk, poor, underachieving populations. But no one really wants to commit to children who are poor, disabled or of color. They don't vote, they don't have money, influence or power. They are refugees in America. And you know what we think about refugees. They are different and dangerous and not our problem.

Once the white suburban families, the middle class, the real Americans were negatively affected by NCLB, the federal government offered flexibility, waivers and alternatives to AYP. And within a few years, the program was shelved. Now we are back to local control and all is well in our world.

Just one problem... the Same Children are Left Behind. Let's call it the SCLB Act.