|

| Oswald Murdered by Ruby - 1963 |

|

| Garner Choked to Death - 2014 |

When I was 10 years old I cried, couldn't sleep and could not make any sense of what happened. I was scared for my family's safety and the country's safety. At the age of 61, I was horrified. Eric Garner was accused by the NYPD of selling single cigarettes on the street. He was frustrated and begged the police to leave him be. When they went to arrest him, it took 5 officers to drop him to the ground. One put him in a choke hold and Garner gasped repeatedly "I can't breathe, I can't breathe" and he died. There had to be another way to deal with this. From my perspective as an urban high school principal, this was an easy situation to manage. There were many ways to de-escalate and resolve what appeared to be an impasse.

|

| Jonny Gammage - 1995 |

|

| Emmett Till - 1955 |

Is it possible to put the hundreds of police/victim incidents into a rational context? I'm not talking about the self defense cases. Or a man waving a gun at the police. Or a gun battle. We're talking about selling cigarettes (Garner), or "driving while black" (Gammage) or walking down the middle of the street with stolen cigars (Brown). We are bombarded by a never ending stream of these stories. To watch a man murdered... and by the police.

Is it racism? Is it fear? And why does the jury always find the people who killed the man innocent? ALWAYS! What are we to make of this? More importantly, what are our children to make of this?

Anyone who denies racism in our society is naive, foolish, ignorant. Both blacks and whites grapple with the vestiges of over 250 years of slavery, followed by 100 years of Jim Crow, followed by 50 years of economic, education and employment inequities. 350 years of treating a race of people like they were subhuman. Conservative Americans can't understand why "blacks" can't be more like whites... more responsible. They are incapable of understanding the effects of the African-American diaspora - the effects of racism, hatred, lack of employment, poor schools, overcrowded jails and harassment on a nationwide scale. They are blind to the emasculation of black men and the sexual exploitation of black women who were enslaved on American plantations. And they can't imagine how this 350 year history could possibly effect the behaviors of the descendents of slaves today.

Are the police racist... some are and many are not. If you watch the Garner video, you sense the police are working on a very superficial level. They want this guy to quit selling cigarettes illegally on the street. He probably is a nuisance to local businesses who made a complaint. They are beat cops who are just looking to clear this man away. Are they racist, angry or looking for a fight? The video would suggest that is not the case. They just aren't going to take no for an answer. Once the police back-up arrives, a total of 5 policemen take the man down. Now the situation takes on a life of its own... that leads to death. The police are trained to be experts at de-escalating difficult situations. They clearly failed. Would they have acted the same way with a white man... my guess is yes. In either case, is killing this man justifiable? NO. This man is selling single cigarettes (although he denies it), the police overreact to a shocking extreme and within minutes he is dead.

Anyone who denies fear in our society is simply blind. The news media, both on television and online, would have you believe that cities are crime filled sinful places. NIght after night the local and national news projects images of black men being led away by police. In isolation, this creates a worldview that is seriously skewed. The Pittsburgh Metropolitan population, primarily white, is being fed a biased and near sighted bad movie. "Blacks are poor, blacks are on drugs, blacks are on welfare, blacks commit crimes". It's an old riff that is filled with both racism and fear. I would suggest our fear is fed through perception not through experience. My acquaintances who live in the suburbs won't let their children ride the PAT buses. Why not? They live in fear.

While census data from the past 30 years indicate some signs of increasing diversity, we still remain a region deeply divided. In 1980, the average white person in the Pittsburgh metro area lived in a census tract that was over 95 percent white. In 2010, that same white person lived in a tract that was about 92 percent white. (Post-Gazette, 8/9/2012)The are two issues that I believe contribute to the victim/police killings. The first is that many white people (including police officers) simply have no day to day interaction with diverse, middle class populations. Most live in segregated communities. In America and certainly in the Pittsburgh Metropolitan area, most communities are segregated by wealth and race. Even in the city it is not surprising to find areas where whites (and white police officers) live in segregated communities. Whether in the suburbs or isolated areas of the city, a substantial number of police officers are not engaging with middle class black citizens like themselves. Lack of day to day interactions with middle class black families causes police perceptions to be skewed to the people they meet in their jobs. Which leads to the second problem.

By definition, an urban police force engages with populations that are in poverty, are unemployed, are less educated, are often engaged in illegal activities and suffer from mental and behavioral health issues. Thus they have a well founded fear and mistrust. And they have few positive interactions to balance their perspective.

However, the police went into their profession with a desire to keep our communities safe knowing they would interact with at risk individuals and criminals on a daily basis. They are professionals who are trained to de-escalate and solve complex problems with a minimum amount of violence. These killings, although a small percentage of the overall policing of America, are abominations, and yet they go unpunished. Cops are good, poor people are bad, you guess who gets the benefit of the doubt. This is an unhealthy situation.

So why did I raise this issue in The Principal's Office? Obviously it is bothering me at a visceral level. The other night I watched Jon Stewart talk about the verdict in the Eric Garner case and it brought him to tears. All he could do was scream... literally. That is what I've been feeling. What can we learn from this madness? Well here is what I have to offer.

First, from a personal perspective, I've lived in Wilkinsburg for over 35 years and worked in city schools for that time. My family has lived, attended school and worked in integrated environments during that time. Wilkinsburg has a reputation for being poor and dangerous. Yet we don't live in fear. Just the opposite. We have friends who are diverse and have the same values that we do. We find that everyone has a simple commonality regarding safety, education, desire to move forward and families that are at the center of their life. Wilkinsburg is portrayed on the news as a terrible place, with crime, bad schools and bad people. This is a small part of a much bigger picture that never gets told. We have had a safe and rewarding life in Wilkinsburg.

|

If your perceptions of black people are limited to the media, than you will be shocked by this chart showing the percentage of black families receiving public assistance. Clearly, the majority of blacks do not receive public assistance of any kind. And surprisingly about the same number of whites receive public assistance as do blacks (http://www.statisticbrain.com/welfare-statistics/).

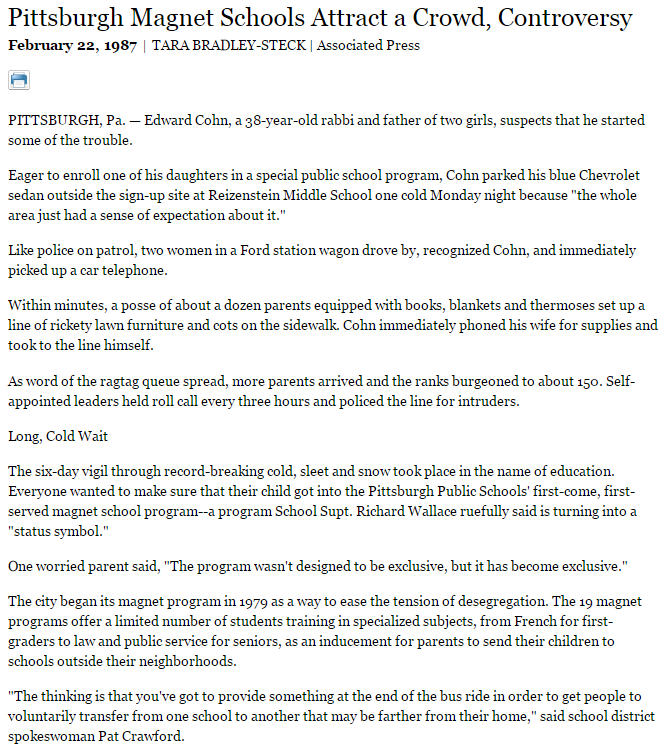

If your perceptions of black people are limited to the media, than you will be shocked by this chart showing the percentage of black families receiving public assistance. Clearly, the majority of blacks do not receive public assistance of any kind. And surprisingly about the same number of whites receive public assistance as do blacks (http://www.statisticbrain.com/welfare-statistics/). Third, let me provide you with some insight into racism and fear from an educational perspective. Pittsburgh is a parochial town. What side of the river you live on and what community you come from often determines your world view. I began teaching in the city schools in 1979 at Brashear High School. The school's history was borne out of forced integration.

In 1971, the Pittsburgh Board of Public Education formally approved construction of the first of five proposed 9-12 Super High Schools to replace the twelve comprehensive secondary schools then owned and operated by the Pittsburgh Public Schools. John A. Brashear High School, the only Super High School to realize fruition, was to be located in the Beechview neighborhood of the South Hills and would integrate 9-12 students from Fifth Avenue Junior/Senior High School, Hill District; Gladstone Junior/Senior High School, Hazelwood; and South Hills Junior/Senior High School, Mount Washington. The undertaking of melding these distinct communities into one was not easy; however combined dedication from progressive civic leaders and educators made Brashear not only a success but, also, a model for social integration and scholastic achievement.Brookline, Beechview and Banksville were three all white South Hills communities on the south side of the Monongahela River. The Hill District was a famous all black community on the north side of the river up the hill. It was made up of both middle class families (Sugar Top) and poorer families (Uptown, SOHO and Center Avenue). And Hazelwood was a very poor ex-steel community that was mixed race on the north side of the river in the flats. It was assumed this would be a volatile student body from a racial, economic and neighborhood perspective. This new Super High School consisted of a beautiful physical plant with amazing programs - a dry cleaning facility, a student run restaurant offering lunch for staff, a computer science magnet, an automobile mechanic and body shop, business labs and great sports teams.

I taught mathematics at Brashear for 5 years. Simply put, the integration model worked. Students were integrated in classes with high expectations for all students. Teachers from the old Fifth Avenue High School in the Hill District helped the Brashear experiment move forward. What I learned in my classroom was that adolescents are experienced based. They talk and interact with their peers and make judgements based on their interactions. Frankly, in my five years at the school, I never had a problem based on race. My colleagues who were at Brashear from the beginning stated that the school had a smooth opening. Students rallied around a great football and basketball team. The school worked. And progress was made against racial stereotypes. When you live, eat and learn with diverse students, your mind opens up. And you begin to cut people a break.

Years later, a few of my students at Brashear, enrolled their own children in my charter school. These were both black and white parents looking to find a quality education for their children. The issue of a mixed race school was not even a concern. Quality was all that mattered. This was the second generation of students who attended a quality integrated school. Race disappeared into the background and our students were able to concentrate on what they should concentrate on: learning, growing and experiencing the richness of our world. They do not fear each other. They hope for a future that is filled with success, prosperity and peace. Many of these students live in integrated communities. And many have friends from the other race. They don't fear each other. They do fear the police.

I don't know if we'll ever live without fear. I believe there will always be people in power who take justice into their own hands. Man's cruelty to man is not new. Frankly, whether you are Black, Jewish, Muslim, Italian, Irish, Mexican or from any immigrant parentage, your people have suffered discrimination and violence. The currency of totalitarian states is violence.

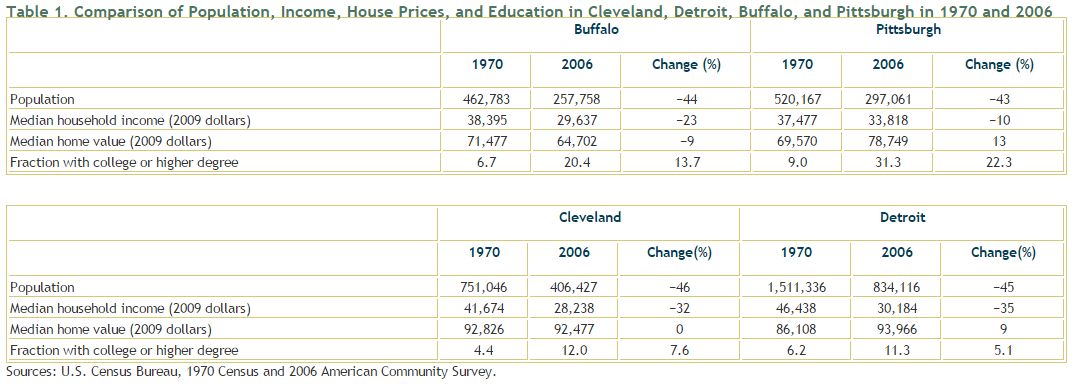

I don't know if we'll ever live without fear. I believe there will always be people in power who take justice into their own hands. Man's cruelty to man is not new. Frankly, whether you are Black, Jewish, Muslim, Italian, Irish, Mexican or from any immigrant parentage, your people have suffered discrimination and violence. The currency of totalitarian states is violence. I believe it will take many more generations living in a diverse country before we get close to equity. It certainly won't happen in my lifetime. Attitudes, beliefs and behaviors change at a snails pace. We often measure change by looking at our grandparents, our parents, ourselves and our children - generations. It's important to note that as racial differences begin to mitigate, we learn that the greatest inequity comes from lack of employment, not the color of your skin.

I believe it will take many more generations living in a diverse country before we get close to equity. It certainly won't happen in my lifetime. Attitudes, beliefs and behaviors change at a snails pace. We often measure change by looking at our grandparents, our parents, ourselves and our children - generations. It's important to note that as racial differences begin to mitigate, we learn that the greatest inequity comes from lack of employment, not the color of your skin.  |

| CBS News |

To keep sane, to sleep at night, to rise above being animals... we must testify, speak out and fight against racism, classism and blatant violence that is the result of ignorance, anger and bias. And most importantly, we must not live in fear.