Some background is in order. In 1984, when I was a mathematics teacher at Brashear High School in Pittsburgh, I said to a friend and colleague, "if we could only teach the same students for four years, we could really raise everyone's level of achievement". My friend agreed, although, of course he stated the obvious drawback to the idea, "what if the kid gets a lousy teacher?". So I put the idea on the back burner and never really revisited it... until 1988. In the spring of 1988 the AFT journal, The American Educator, published an article entitled, CREATING A SCHOOL COMMUNITY: One Model of How It Can Be Done, An Interview with Anne Ratzki. The article described a group of German schools in grades 5-10 where teams of teachers stay with students for 6 years. Looping. Their results were spectacular:

In 2001, when we were designing City Charter High School, I revisited the idea. We (the co-founders of the school and the advisory committee authoring the charter) were developing the school on a number of assumptions based on our experiences as teachers in the Pittsburgh Public Schools:The Koln-Holweide school whose student population was composed of a fairly equal mix of high- middle- and low- ability students; a substantial proportion---one third--of Turkish students, Germany's major minority population; and a representative mix from middle- and lower-income households. Yet only 1 percent of the school's students drop out, compared to a national West German average of 14 percent; and 60 percent of its students score sufficiently well on high school exit exams to be admitted to a four-year college, compared to a national average of only 27 percent. Moreover, the school suffers practically no truancy, hardly any teacher absenteeism, and only minor discipline problems.

- The vast majority of urban students (> 65%) come from single parent families, live in poverty and have few opportunities to develop lasting relationships with adult role models.

- Most urban students move from school to school and experience a transient education.

- Most urban students need to build a trusting relationship with their teachers before they are receptive to learning.

- All students can succeed when placed in a safe, nurturing and supportive environment to learn in.

We felt that looping addressed many of these assumptions. Thus we implemented it at City High. When a student enters City High in 9th grade, they immediately join a group of 160 students and 12 adults: 9 teachers - Math, Science, English, Social Studies, Tech (2), Research, Special Education (2) and 3 Teaching Associates. This group of twelve educators stays with the students for four years. The student has the same content area teacher, the same faculty advisor, the same support staff for four years. The grade level team becomes a community.

Before I go into the effect of looping on everyone concerned, I should address my friend's question "what if the student gets a lousy teacher?". This question is predicated on a very cynical view of schools. The idea is that if there is a mediocre teacher, it is best to limit that person's effect on a given student to a single year. Or in an even more cynical view, it allows the attentive parent to pressure the principal to transfer the student out of that teacher's class. Students with less attentive parents suffer the consequences. So by changing teachers year to year we hope that the student will have enough "good teaching" to succeed. This is, in essence, burying the problem.

I would suggest that by using looping, we are bringing the issue of mediocre teaching to the surface. When a teacher struggles, and is not doing a good job, it is the responsibility of the administration to support that teacher and get them to improve or rate their work unsatisfactory ultimately leading to being fired. Looping forces accountability on everyone concerned, but particularly the administration. In a looping scenario, a poor teacher for 4 years would have a devastating effect on students. Thus, the administration must see that one of it's most important responsibilities is to hire, nurture and develop quality teachers.

The follow up question of "what if the student doesn't get along with the teacher (or visa versa)?" raises a key reason for doing looping. The life skill of being able to navigate interpersonal relationships in the workplace is a key to success. When a student has a problem with a teacher, it is important for the student and teacher to work the situation out. In a Looping context, the administrator often facilitates conversations between students and faculty in order to teach communication skills, problem solving and mutual respect. In 12 years of looping at City High, it was an extremely rare experience to not resolve these problems.

Looping was implemented at City Charter High School in 2002 and we now have 12 years of data to learn its effect. Clearly, the primary benefit of looping is accountability. Since the players remain the same, the collaboration between the parent, student, teacher and administrator is key. Everyone is accountable. And it is to everyone's advantage to develop a working communicative relationship.

This accountability leads to much higher student engagement and achievement than one would find in a traditional urban high school:

Here are some examples of how Looping changes the operations, culture and attitudes in an urban high school.

So when I heard the teachers talking about what they had learned over four years, it was imperative that we built on lessons learned. That summer, the 12th grade teachers went on a one week retreat to plan for their looping back to 9th grade. They discussed issues of management (faculty responsibilities and roles), support, lesson design, etc. They also discussed the fact that for the first time they were not teaching their content in a vacuum, but truly understood the trajectory of the four year content strand. They then embarked on another four years. To make a long story short, these same teachers who graduated 93 students in 2006, graduated 115 students in 2010. And believe it or not, the four cohorts that were in their second loop graduated 115 students. The four looping faculties increased the number of students staying at City High and graduating by over 20%. And believe it or not, we anticipate the third trip through the loop (for the faculty) will graduate over 125 students. These increases are due to the knowledge gained by teachers about the possibilities that looping provides and their understanding of students' needs. The effect of looping on the teachers is, in my opinion, the most powerful aspect of its use.

The effect of looping in an urban high school is to change the culture. Instead of teachers teaching content, they are teaching students. Instead of blaming past teachers, parents, the community and laziness for the poor achievement of their students, they take responsibility for motivating, empowering and succeeding with their students. Instead of students being passive learners who make excuses for why they can't succeed, they buy in and work hard to reach their goals and dreams. And instead of staying in their office and doing paperwork, administrators work at hiring the highest quality teachers, creating working/collaborative faculty teams and helping needy teachers improve. Creating a culture of collaboration, accountability and results is compelling. And it doesn't cost any extra money. It just means we have to change.

Before I go into the effect of looping on everyone concerned, I should address my friend's question "what if the student gets a lousy teacher?". This question is predicated on a very cynical view of schools. The idea is that if there is a mediocre teacher, it is best to limit that person's effect on a given student to a single year. Or in an even more cynical view, it allows the attentive parent to pressure the principal to transfer the student out of that teacher's class. Students with less attentive parents suffer the consequences. So by changing teachers year to year we hope that the student will have enough "good teaching" to succeed. This is, in essence, burying the problem.

I would suggest that by using looping, we are bringing the issue of mediocre teaching to the surface. When a teacher struggles, and is not doing a good job, it is the responsibility of the administration to support that teacher and get them to improve or rate their work unsatisfactory ultimately leading to being fired. Looping forces accountability on everyone concerned, but particularly the administration. In a looping scenario, a poor teacher for 4 years would have a devastating effect on students. Thus, the administration must see that one of it's most important responsibilities is to hire, nurture and develop quality teachers.

The follow up question of "what if the student doesn't get along with the teacher (or visa versa)?" raises a key reason for doing looping. The life skill of being able to navigate interpersonal relationships in the workplace is a key to success. When a student has a problem with a teacher, it is important for the student and teacher to work the situation out. In a Looping context, the administrator often facilitates conversations between students and faculty in order to teach communication skills, problem solving and mutual respect. In 12 years of looping at City High, it was an extremely rare experience to not resolve these problems.

Looping was implemented at City Charter High School in 2002 and we now have 12 years of data to learn its effect. Clearly, the primary benefit of looping is accountability. Since the players remain the same, the collaboration between the parent, student, teacher and administrator is key. Everyone is accountable. And it is to everyone's advantage to develop a working communicative relationship.

This accountability leads to much higher student engagement and achievement than one would find in a traditional urban high school:

- 94% daily attendance;

- 96% graduation rate;

- #1 High School in Pennsylvania with respect to low-income student performance and #6 with respect to African-American student performance (PENNCAN);

- 30% higher African American eligibility for the Pittsburgh Promise than the Pittsburgh Public Schools;

- Graduation from 4 year colleges at a rate 20% higher than the national average.

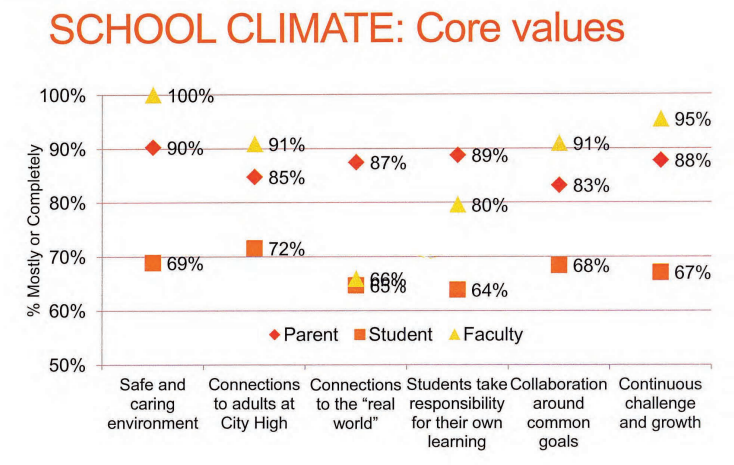

A deeper look at the school with respect to looping suggests that parents, teachers and students find the school to be supportive, connected and collaborative. The following survey data from the 2012-2013 City High annual report shows that approximately 9 out of 10 parents, 9 out of 10 teachers and 7 out of 10 students believe the school climate to be conducive to success.

Here are some examples of how Looping changes the operations, culture and attitudes in an urban high school.

The 9th to 10th Grade Transition

Ninth grade is always a difficult year for students and teachers. It is filled with adjustment issues, maturity issues and fear of being able to succeed in high school. Much of the year is spent building relationships (with both students and teachers), learning routines and forming study skills (i.e. learning how to learn.) In traditional schools, when you come back from summer vacation in 10th grade, you have a new set of students and teachers to become acclimated to. This often results in the same 9th grade issues of developing trust, learning routines unique to the teacher and managing the social aspects of high school. Using looping, this transition to 10th grade is eliminated. On the first day back to school, students greet their teachers and classmates. Everyone knows each others names, personalities, likes and dislikes. Teachers know their students learning styles and knowledge base. At 8:00 A.M. on the first day back from summer vacation, everyone is ready to go and promptly begins work. There are no schedule changes during the first month of school since you are on a team, block scheduled and know who your teachers are. This is in contrast to traditional school settings where September is a time of tumult - schedule changes, learning names, trying to figure out what students know and building trust. I would suggest that the month of September at City High is very productive and reinforces the grade level community that students and staff are part of.The Effect of Looping on Teacher Expectations

After the graduation of our first cohort of students, the 12th grade faculty went out to lunch. At lunch I was listening to a number of our teachers talk and it was a real eye opener. "Can you believe that so and so graduated? I never thought he would make it. If I knew then what I know now about teaching kids for 4 years, we could have saved so many more students." I never really thought about looping with respect to the effect it might have on a teacher's belief system. When the school opened the class size was 160 students. Of that number, 93 graduated four years later. The 63 who didn't graduate transferred to local public schools, mainly because they felt City High was too challenging. In fact, the first four graduating classes (loops) had the same number of graduates 93. This had to be more than a coincidence.So when I heard the teachers talking about what they had learned over four years, it was imperative that we built on lessons learned. That summer, the 12th grade teachers went on a one week retreat to plan for their looping back to 9th grade. They discussed issues of management (faculty responsibilities and roles), support, lesson design, etc. They also discussed the fact that for the first time they were not teaching their content in a vacuum, but truly understood the trajectory of the four year content strand. They then embarked on another four years. To make a long story short, these same teachers who graduated 93 students in 2006, graduated 115 students in 2010. And believe it or not, the four cohorts that were in their second loop graduated 115 students. The four looping faculties increased the number of students staying at City High and graduating by over 20%. And believe it or not, we anticipate the third trip through the loop (for the faculty) will graduate over 125 students. These increases are due to the knowledge gained by teachers about the possibilities that looping provides and their understanding of students' needs. The effect of looping on the teachers is, in my opinion, the most powerful aspect of its use.

Graduation

Graduation is on the third Saturday of June at the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall in Oakland. All aspects of the ceremony - speakers, ushers, greeters, choir and hosts for the event - are run by the students. As you might imagine, this is a big day for the graduates, their families and their teachers. These students and their teachers have lived together for four years. They are invested in each other. And they know that walking across the stage at City High graduation is a huge accomplishment. As each student is called forward to receive their diploma, their image is put on the large screen with their college, job or future plans listed. The audience is made up of over 2000 relatives and friends. Many of the students are the first in their family to graduate high school and many more will be the first to graduate college. The audience does not clap or yell for the individual student. The student walks up on the stage where the administration and their teachers stand to congratulate them and wish them well for the future. Everyone hugs, everyone cries, everyone is bursting with pride. A lifelong connection has been made between adult and child, teacher and student. When the name of the last student is called up and he/she crosses the stage, the audience and the staff stand, clap and scream their approval. And then everyone goes outside of the hall and throws their graduation cap into the air. Afterward, the faculty goes out for lunch (and a few drinks) and begins to think about their students who graduated and what they will improve when they loop back to 9th grade.The effect of looping in an urban high school is to change the culture. Instead of teachers teaching content, they are teaching students. Instead of blaming past teachers, parents, the community and laziness for the poor achievement of their students, they take responsibility for motivating, empowering and succeeding with their students. Instead of students being passive learners who make excuses for why they can't succeed, they buy in and work hard to reach their goals and dreams. And instead of staying in their office and doing paperwork, administrators work at hiring the highest quality teachers, creating working/collaborative faculty teams and helping needy teachers improve. Creating a culture of collaboration, accountability and results is compelling. And it doesn't cost any extra money. It just means we have to change.

If you are interested in a deeper analysis of Looping at City High, you can read a white paper on the topic written by Dr. Catherine Nelson, an outside evaluator of the school. (http://cityhigh.org/publications/looping-june-2011/)