Today's blogpost tells the story of the attempted integration of the Pittsburgh Public Schools from 1964 to the present. It gives background as to how we got to where we are today and points out an inherent issue we have in our country - a deep desire by many citizens to live in segregated communities and attend segregated schools. Some would call this racism, others would attribute it to fear. Either way, segregation is not a PUMP, it is a FILTER. Note that this post contains a number of original documents in an attempt to capture the attitude of the times.

1954

Pittsburgh, 71,000 Students, 74% white, 26% black

|

| AP WAS THERE: Original 1954 Brown v. Board story By HERB ALTSCHULL, The Associated Press: May 17, 1954 |

The Supreme Court ruled today that the states of the nation do not have the right to separate Negro and white pupils in different public schools. By a unanimous 9-0 vote, the high court held that such segregation of the races is unconstitutional. Chief Justice Warren read the historic decision to a packed but hushed gallery of spectators nearly two years after Negro residents of four states and the District of Columbia went before the court to challenge the principle of segregation. The ruling does not end segregation at once. Further hearings were set for this fall to decide how and when to end the practice of segregation. Thus a lengthy delay is likely before the decision is carried out.This landmark decision overruled the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling that allowed "separate but equal" accommodations in public facilities, such as bathrooms, water fountains and in the case of Plessy, railroad cars. Because Plessy dealt with public areas where people came together out of necessity, putting integration into action was somewhat easier - when blacks and whites came together in public spaces, both would have access to the same facilities. Integrating schools would be a far greater challenge since most people lived in segregated communities and attended their neighborhood schools. The races did not come together out of necessity for school. Thus school integration would have to be a more deliberate, active event. Therein was the challenge.

1964

10 years after Brown v. Board of Ed.

Pittsburgh, 77,000 Students, 109 schools, 63.3% white, 36.7% black

In the 1960's when the federal Civil Rights Act was passed, Pittsburgh was a segregated city by neighborhood and school. And white flight to the suburbs had slowly begun. The white population of the city schools decreased by 22% from 1945 to 1965. In 1965 the district authorized a report - The Quest for Racial Equality in the Pittsburgh Public Schools: Annual Report 1965. The chart below from the report provides the trend that began in the district after World War II.

As one can see the "Negro" population in the district increased from 18,356 when Brown v. Board of Ed. occurred to 28,242 10 years later. The report goes on to state that the district had segregated schools. The following graph from the report provides a baseline for student achievement in segregated elementary schools. The lowest achieving elementary schools were nearly all black and the highest achieving elementary schools were all white. Note that 2/3 of the schools in Pittsburgh were achieving at a level higher than the National median.

|

One can also see from the report that Pittsburgh did not suggest integrating its schools to address the challenge created in the 1954 Supreme Court ruling. The amazing explanation below states that 10 years after Brown v. Board or Ed., Pittsburgh was not ready for integration. Compensatory education is another name for trying to make separate equal. You sense from the tone of the explanation that in 1964 district leaders did not believe the community would tolerate any attempt at integration. They suggested this would occur only when there existed a "newly enlightened society".

1977

1977

23 years after Brown v. Board of Ed.

Pittsburgh, 59,000 Students, 97 schools

|

| Post Gazette, Feb. 26, 1977 |

Starting with the 1965 report on Racial Equality, the Pittsburgh Board of Education committed itself to compensatory methods for improving Black academic achievement. These included more black staff/teachers, pre-school (Head Start), culturally sensitive books and resources, increased college opportunities, vocational technical training and creating an open school policy allowing for voluntary transfers to schools where room existed.

In 1968 the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission (PHRC) determined that Pittsburgh was not attempting to integrate and therefore asked for a desegregation plan to create racial balance in the district. The district provided a plan that was based on voluntary integration using magnet schools and building new schools and adjusting feeder patterns. The PHRC was dissatisfied and ordered the district to put a plan in place by 1971-72. There was a huge amount of community and parent push back not to integrate the district. In one case, white students were reassigned to a predominantly black school (Knoxville) with disastrous results. The district submitted a plan in 1973 that the parents opposed because it went too far and PHRC denied because it did not go far enough. This battle went back and forth for over 7 years. The district continued to push for volunteer integration and the public demanded the schools to not force integration. PHRC and the courts demanded a comprehensive plan. While this struggle continued, whites were fleeing to the suburbs.

In 1980, the district student population was down to 48,000 students. PPS implemented an integration plan based on new schools (e.g. Brashear, Reizenstein), new feeder patterns and magnets. The Brashear High School plan was a perfect case in point. The old Fifth Ave. High School in the black community called the Hill District was falling apart. The same could be said of Gladstone High School in a very poor community called Hazelwood. And South Hills High School in a white community was in need of numerous upgrades. The district chose to build a brand new state of the art comprehensive high school in the South Hills, a white community. PPS closed the other high schools, created Brashear High School and bused students to the school. Over 60 buses arrived every morning with students from 5 neighborhoods. Faculty had to petition to work at Brashear and were hand selected in an attempt to create a model school. The school opened in 1976. (An aside... I taught mathematics at Brashear from 1980 - 1986.) The school was a magnificent structure, the faculty was engaged and the programming included vocational options like a student run restaurant, auto mechanics and body repair, dry cleaning, computer science, excellent sports and a quality academic program. This was one of the first real attempts at integration in the district. Although I don't have data to confirm my impression as a teacher at Brashear, I believed that the school worked. There was little or no violence, minimal racial tension and there was the beginning of a sociological learning process for how the races could work side by side and get educated.

The PHRC went to court, but lost and Pittsburgh's plan went forward. Magnets, voluntary new school programs, were done by signup and were racially balanced. Parents stood in line for days waiting to get their children into these select schools. The magnet programs flourished. The three distinctions of the magnets were 1. they were racially balance (aligned with the district demographic), 2. they had a specific emphasis such as foreign language, or math and science or a classical academy and 3. parents had to wait in line to get in. Thus there appeared to be a level of exclusivity. Magnet schools tended to have motivated staff, interested parents and were integrated. Their achievement scores were superior to the district's comprehensive feeder pattern schools. However, the majority of non-magnet schools remained segregated. Brashear and Reizenstein were the exception.

2000

46 years after Brown v. Board of Ed

Pittsburgh, 39,000 students, First Charter School is approved

In the late 1990's three issues came together to change the urban education landscape. The first major change nationally occurred during the late 1980s and 1990s. During that time, the Supreme Court ruled that the methods used for integration of schools were unconstitutional. After a decade of controversial attempts at integration through busing, school districts began to back pedal. A Harvard University Civil Rights Project paper written by Gary Orfield - SCHOOLS MORE SEPARATE: CONSEQUENCES OF A DECADE OF RESEGREGATION details this return to segregated schools.

Almost a half century after the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that Southern school segregation was unconstitutional and “inherently unequal,” new statistics from the 1998-99 school year show that segregation continued to intensify throughout the 1990s, a period in which there were three major Supreme Court decisions authorizing a return to segregated neighborhood schools and limiting the reach and duration of desegregation orders. For African American students, this trend is particularly apparent in the South, where most blacks live and where the 2000 Census shows a continuing return from the North. From 1988 to 1998, most of the progress of the previous two decades in increasing integration in the region was lost. The South is still much more integrated than it was before the civil rights revolution, but it is moving backward at an accelerating rate.The second change locally could be seen in the district's demographics. By the year 2000, the Pittsburgh Public Schools lost 50% of its students since the discussion of integration began in the mid-1960's. The middle class voted with their feet... they would rather move than attend integrated schools. Racism and fear was still a major issue in our country and in Pittsburgh. When people of means leave an urban school district, the remaining population, on average, are poorer and have more risk factors that hinder education. Thus, when one focuses on test results, it appears that the schools are doing a much worse job than they had in the past.

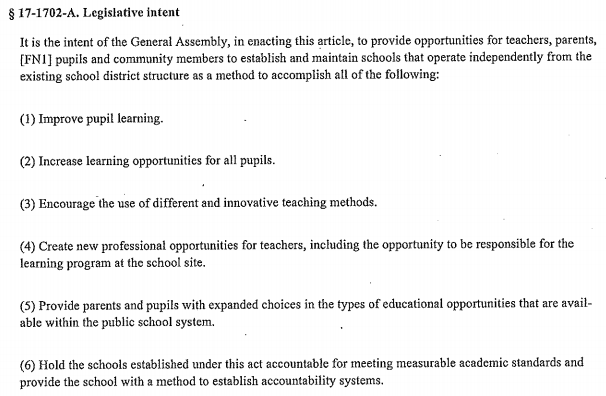

The third change at the state level was the passage of the PA Charter School Act in 1997. This was followed by the founding of the first charter school in Pittsburgh - Northside Urban Pathways - in 1998. The state legislature passed the charter school law as a reaction to over 40 years of failed efforts to integrate public schools and the perception that public schools, particularly in urban areas, were not doing a good job and were not willing to change.

I would suggest that Charter Schools were the result of "the perfect storm" in urban public education. Middle class students leave the district in droves, remaining students are much more at risk due to poverty, crime and crumbling neighborhoods and district schools are slow to understand that the current education model (that achieved above the National Median in 1964) was woefully inadequate with the current population. So the state created an alternative to try and jump start "the use of different and innovative teaching methods".

There were many who believed that Pittsburgh charter schools would take the best students, thereby hurting the public schools. That, of course, should have been the same argument they had against district magnet schools. But that argument was not made because magnets are part of the school district, using district employees and attempting to comply with the state Human Relations Commission requirements. A study of local charter school demographics (in my last blogpost) shows that the district's magnet high schools, comprehensive schools and charter schools all have poverty levels over 50% (CAPA is the exception.) Clearly the tension created by the charter schools has less to do with their results and their student body and more to do with their funding. It is estimated that the charter schools in Pittsburgh take over $50 million from the district annually.

2014

60 Years after Brown v. Board of Ed. Pittsburgh, 24,000 Students, 50 schools, 54% black, 34% white.

First, you can see that the district, no matter what kind of school, has students with a high level of poverty (between 62 and 89%). This is due mainly to middle class flight to the suburbs. Note that there are only 1/3 as many students in the district than when Brown v. Board of Ed. occurred in the 1950's.

Second, you can see that district magnet schools, partial magnets and integrated schools are very close to the district average in racial balance (54% black, 34% white.)

Third, note that the magnet schools and white schools have much higher PSSA scores than the other schools in the district. Also note they have the lowest poverty levels (62-64%).

Fourth, note that 30% of the students in the district attend segregated schools. Black schools have much lower PSSA scores than White schools. If you look just at the White or Black schools you will note that there is a 25% difference in their poverty statistics (64% vs. 89%).

So currently the District is a mixed bag of magnets, integrated schools and segregated schools. The white schools and the full magnet schools have the highest achievement. Some of this is attributable to their having less students in poverty. And in the case of full magnets, the filter of choice - meaning having parents that actively choose a school, appears to have an impact on achievement.

The Takeaway... The Future

Brown v. Board of Ed. was a seminal moment in our history. It stated clearly that all students deserve a quality education and providing separate buildings and programs by race was/is not acceptable. Pittsburgh made a concerted effort to desegregate their schools through choice options such as magnet schools and building new schools with integrated feeder patterns. 60 years later segregated Pittsburgh neighborhoods still exist and segregated schools still exist. 60 years later we are still waiting for the "newly enlightened society".The growth of the suburbs changed the playing field with respect to education. In a mobile society with a strong middle class, people will live where they want and educate their children as they choose. When a school district drops to 1/3 of its original size, and the suburbs attract the wealthiest and most mobile of the population, it creates an extremely challenging problem. I wish it were as easy as integrating every school in order to raise our achievement. In 1964, Pittsburgh had 67% of its elementary schools score above the National Median. In 2013, Pittsburgh had only 20% of its schools score above the Pennsylvania average. It is easy to see that Westinghouse High School is an all black school and has one of the lowest achievement levels in the state. It provides justification for the racists and their stupid beliefs that a race can be inferior. It is much harder for them to understand why Brashear High School is an integrated school with a majority white population and also has one of the lowest achievement levels in the state. Urban schools have been abandoned. To grapple with urban education is to grapple with poverty and a class society. What was once a racial problem appears to have become a socioeconomic problem. Employment, poverty, broken families all have a deep effect on educational achievement.

If you wanted to integrate schools now, you would have to do it on a county level, meaning you would have to involve the suburbs. An attempt in that direction was made with the creation of the Woodland Hills School District - three poorer school districts (Braddock, Rankin and Swissvale) and two wealthier school districts (Edgewood and Churchill.) It was a valiant effort, but the middle class began to move away or avail themselves of private schools and the district slowly fell apart. Their achievement scores have steadily dropped over the years and are similar to Pittsburgh's.

We can continue to wait for a "newly enlightened society" or we can learn from schools that succeed in the urban core. They do exist. They do things differently. They are leading the way towards empowering our urban youth. They will be the focus of my next blogposts.

*For the sake of this blogpost, I took the school district data and broke schools down into the 5 categories listed.

- Full magnets have no feeder patterns, they are completely filled by lottery (e.g. CAPA, Obama, Montessori).

- Partial magnets have a feeder pattern, but have a unique program within its school that students outside of the feeder can apply to (e.g. the engineering magnet at Allderdice.)

- Integrated comprehensive schools are within one standard deviation of the the district's mean racial demographic (e.g. Arlington K8, Westwood ES)

- White schools are neighborhood schools with a white population that is over one standard deviation above the district demographic (e.g. Southbrook MS, Brookline ES).

- Black schools are neighborhood schools with a black population that is over one standard deviation above the district demographic (e.g. Mller ES, Westinghouse HS).